An ASYLUM SEEKER is a person who has sought protection as a refugee, but whose claim for refugee status has not yet been assessed.

A REFUGEE is someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war or violence.

A refugee has a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group.

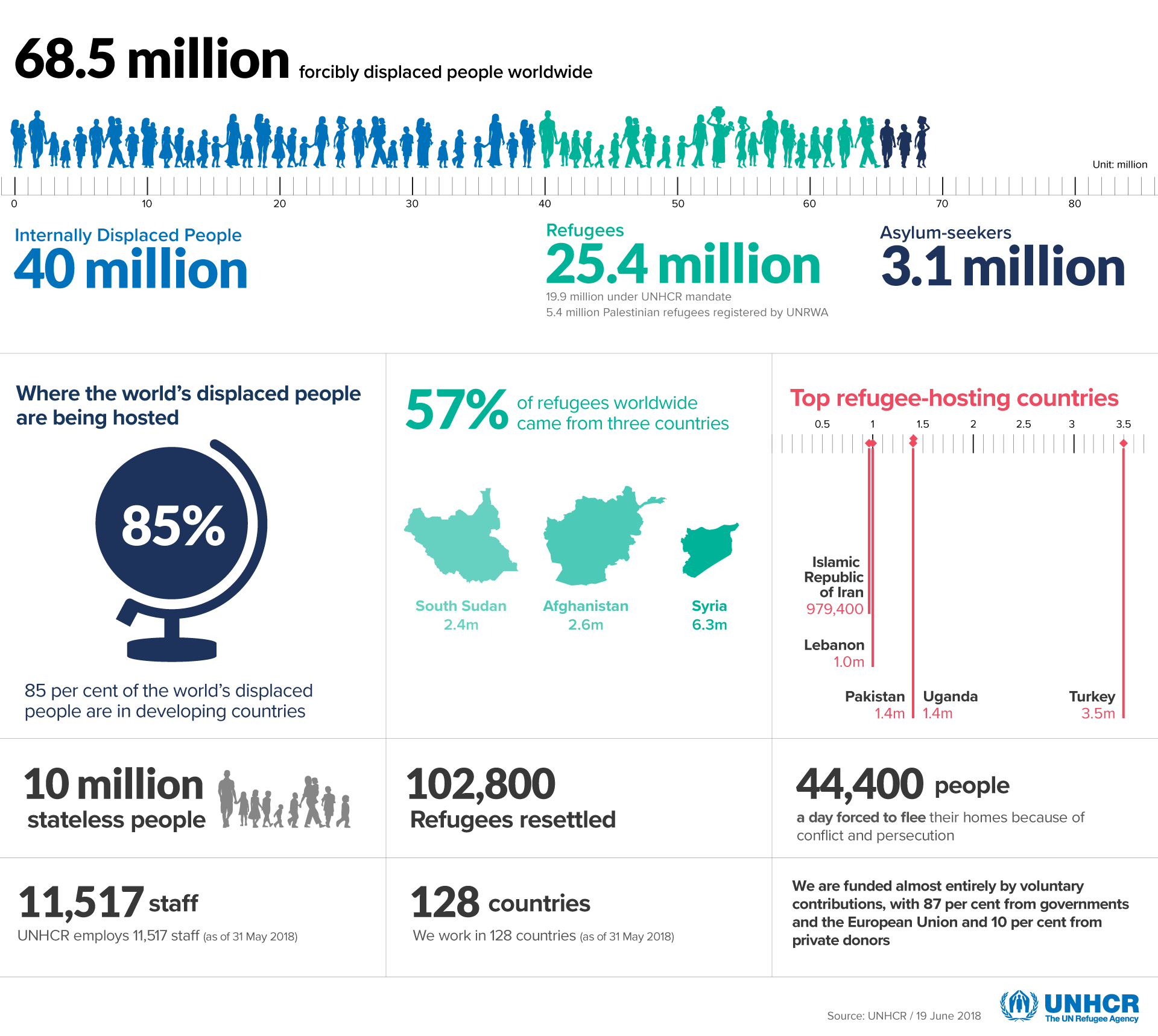

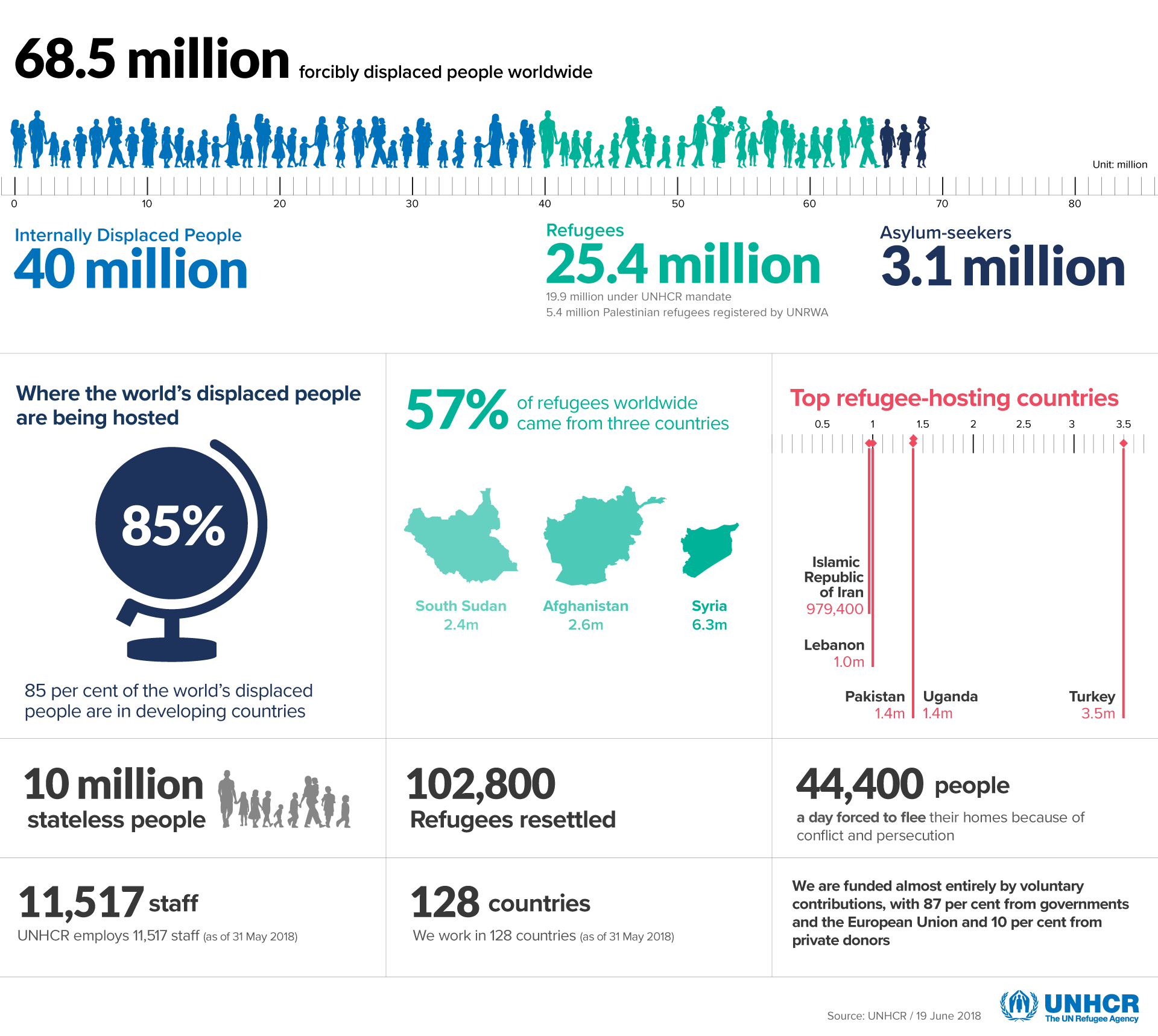

There are now more people displaced in the world than ever before. Today there are 68.5 million forcibly displaced people worldwide, 52% of whom are children. The United Nations helps these people find new homes by working with countries like Australia. However, not all countries will accept refugees, and others may take many years to resettle them. It is a sad truth that many refugees have spent their whole lives in refugee camps.

In keeping with The Migration Act 1958 when refugees arrive in Australia without a visa Seeking Asylum, they are sent to onshore and offshore immigration detention centres until they are granted or denied a visa.

Source: Asylum Seekers and Refugees Guide (August 14 2015).

AUSTRALIA: Current Statistics

As of August 2018 there were…

1,347 People in Australian Detention Centres

376 of these people arrived via boat or air without visas

971 had visas cancelled or overstayed

189 Refugees and asylum seekers held in the Nauru Regional Processing Centre.

361 Refugees and asylum seekers in detention centres on Manus Island.

170 Families were being kept on Nauru as of 26 February 2018, 99 of whom had 158 minors.

Some refugees and asylum seekers have been brought from the offshore detention centre to Australia for medical treatment.

On average, these refugees spend 436 days in detention centres.

Source: Statistics — Asylum Insight(25 August 2018) & Operation Sovereign Borders and offshore processing statistics (3 August 2018).

Source: UNHCR Global Trends 2017

Source: UNHCR Global Trends 2017

VISAS

A Temporary Protection Visa is a temporary visa for refugees who come by boat and claim to be seeking asylum. It provides protection for three years, but does not ensure permanent protection

Safe Haven Enterprise Visas are another type of temporary visa granted to asylum seekers who come by boat. This visa grants 5 years protection to those who intend to study or work in regional Australia.

A ‘Bridging Visa E’ is a temporary visa permitting a refugee stay in Australia only while arranging immigration, making arrangements to leave, or waiting on an immigration decision.

Sources: Bridging visa E – BVE (subclass 050-051) & What is a Temporary Protection Visa (TPV) or a Safe Haven Enterprise Visa (SHEV)? (2017, September).

Between January and June 2018 in there were:

5,0172

Temporary Protection Visas granted

2,488

Temporary Protection Visas denied

7,872

Safe Haven Enterprise Visas granted

2,637

Safe Haven Enterprise Visas denied

17,420

Visa E applicants, 2,916 of whom are children

In 2016-2017 there were:

13,760

Permanent humanitarian visas granted by the Australian government, excluding refugees from the Syrian and Iraqi humanitarian crisis

21,968

Permanent humanitarian visas were granted, including visas delegated to refugees from the Syrian and Iraqi humanitarian crisis

There are 18,750 visas budgeted for in 2018-2019

Source: Statistics — Asylum Insight(25 August 2018).

COSTS

Nauru and Manus Island have cost the government approximately:

$5 billion

Cost of Nauru and Manus Island during the 2017-2018 financial year:

$1.44 billion

The 2018-2019 budget for Nauru and Manus Island detention centres is estimated to cost:

$759.58 million.

Between September 2013 and August 2018 there have been:

741 voluntary returns by refugees, 31 of whom left in August 2018

20 involuntary returns

In 2018, only 1 boat of 17 people arrived in Australia. The people in it were sent to Christmas Island.

Since 2010 there have been 37 deaths in Australia’s onshore and offshore detention centres, including 16 confirmed suicides.

Source: Statistics — Asylum Insight (25 August 2018).

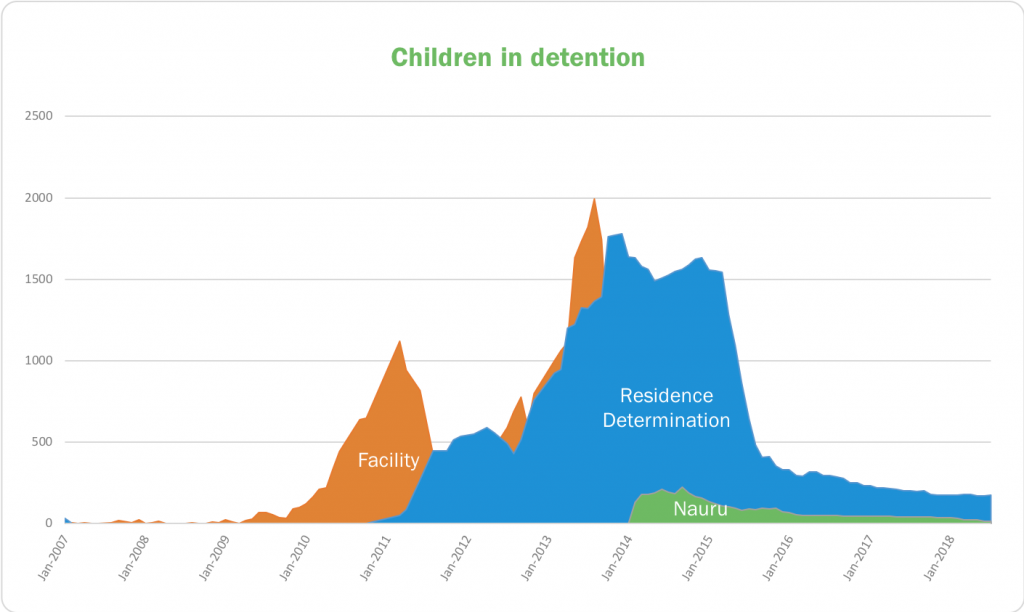

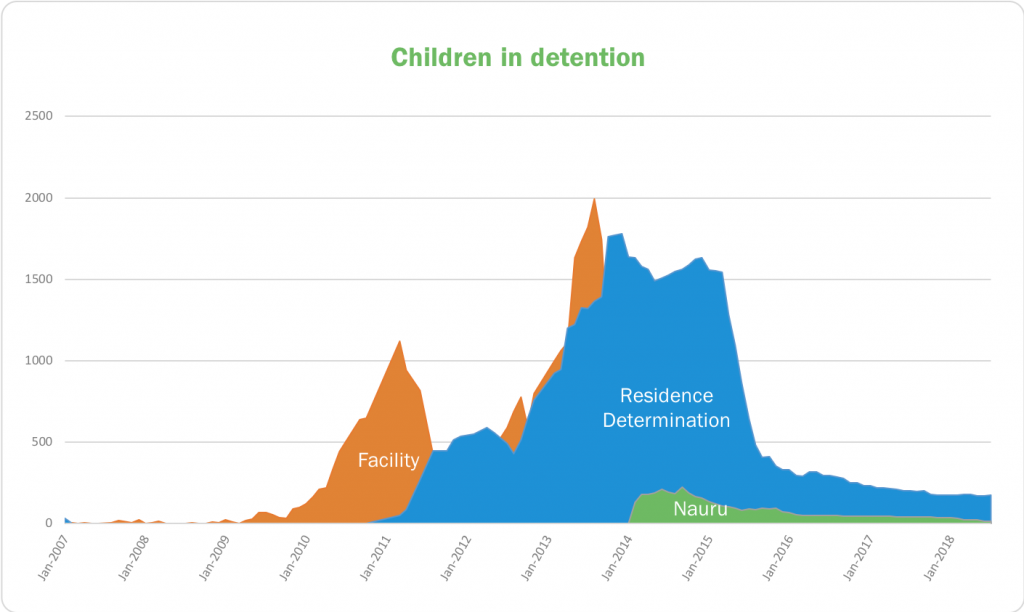

Children In detention

IMPACT OF DETENTION

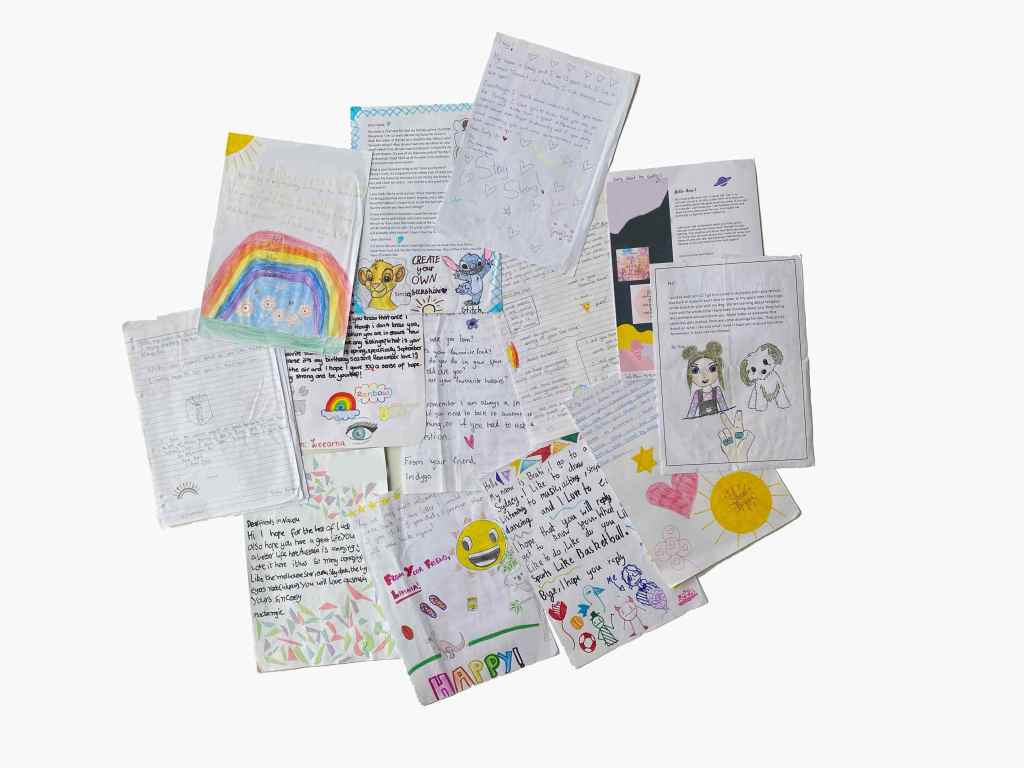

Refugee children experience significant challenges when fleeing their homeland and resettling in a country such as Australia. Many refugee and asylum seeker children who come to Australia end up in a refugee camp in immigration detention.

34 per cent of children in detention have been found to suffer serious mental health issues, compared with only 2 per cent of Australian children.

Detention is an especially damaging experience for children as it deprives them of the opportunities of play, exploration, growth and learning necessary for normal development. Children in detention experience significantly higher rates of mental health issues than children in the mainstream community.

In September 2018, approximately 30 refugee children on Nauru were diagnosed with Trauma Withdrawal Syndrome, or Resignation Syndrome, a rare psychological and physical life-threatening condition causing children to withdraw from life, to the point of becoming unresponsive, unable to eat, drink or toilet themselves until they fall into a catatonic state (Baker, 2018).

The Australian Federal Court has now ruled on several occasions that children with Resignation Syndrome and other life-threatening situations be brought to Australia for immediate medical care along with their families. A recent example is the 12-year-old boy airlifted to a hospital in Brisbane with resignation Syndrome after living on Nauru for the past 5 years (Randall, 2018).

There have been increasing reports of children as young as 7 attempting suicide repeatedly. Children have doused themselves in petrol in attempts to self-immolate. Others have swallowed razors and stones. Others have attempted to overdose, jump from high places or hang themselves (Refugee Council of Australia, 2018).

A number of children are suffering from nightmares of “blood and death”, hallucinating and self-harming (Randall, 2018). It has become commonplace to receive reports of children hallucinating, socially withdrawing, becoming unable to speak or expressing the wish to die(Refugee Council of Australia, 2018).

Many of these children have spent their whole lives on Nauru. Others have spent their most formative years in these traumatic conditions.

Source: Refugee Council of Australia.

Source: Refugee Council of Australia.

WORLDWIDE

In 2017 52% of forcibly displaced people were children under 18 years.

Many of these children will spend their entire childhood, in countries that do not give them full human rights. They are often unable to go to school.

There are 173,800 unaccompanied refugee children who have been separated from their families.

![]()

Source: UNHCR, (2017). Global Trends 2017

AUSTRALIA

70

Children in Detention on Nauru.

2,916

Bridging Visa E applicants who are children

Source: Statistics — Asylum Insight (25 August 2018).

GLOBAL SCALE

Refugees are people who have been forced to flee their countries because of persecution, war or violence. They need to seek help from the governments of other countries.

Refugees often travel to nearby countries to seek safety. These countries are often poor and do not have the money to support the refugees, and sometimes they are unwilling to integrate them into their own communities. This means refugees end up living in refugee camps. Refugees in these camps live in poverty. Most children do not go to school. Refugees live in these camps, sometimes for years, until they are accepted to live in a country like Australia. Some refugees never leave the camps.

In 2017, GLOBALLY, there were:

102,800 refugees resettled in third countries during 2017 (This figure has reduced by 46% since 2016, as forcibly displaced people worldwide increased by 2.9 million in 2017 alone.)

40.0 million internally displaced people

16.2 million newly displaced people in 2017 including…

11.8 million newly displaced internally &

4.4 million newly displaced refugees and asylum seekers

16.9 million (85% of refugees) refugees hosted by developing regions

5 million displaced people returned

44,400 new displacements every day

Source: UNHCR Global Trends 2017

Bibliography & Useful Links

Asylum Insight — Facts and Figures, (2018, 25 August). Retrieved from https://www.asyluminsight.com/statistics/#.W8aTXxMzZmA

Australian Human Rights Commission, (2015, August 14) Asylum Seekers and Refugees Guide. Retrieved from, https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/asylum-seekers-and-refugees-guide

Baker, Nick, (2018). SBS, retrieved from https://www.sbs.com.au/news/coma-like-epidemic-affecting-30-children-on-nauru

Befriend a Child in Detention (2016). Impact of Detention on Children, Retrieved from

https://befriendachildindetention.wordpress.com/impact-of-detention-on-children/

Department of Immigration. (2018). Immigration Detention and Community Statistics Summary. Retrieved from, https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/statistics/immigration-detention-statistics-june-18.pdf

Farrell, P. Evershed, N. and Davidson, H. (2016, August 10), The Nauru Files. The Guardian, retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/aug/10/the-nauru-files-2000-leaked-reports-reveal-scale-of-abuse-of-children-in-australian-offshore-detention.

Home Affairs. (2018). Bridging visa E – BVE (subclass 050-051). Retrieved from, https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/trav/visa-1/051-

UNHCR, (2017). Global Trends 2017. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/5b27be547/unhcr-global-trends-2017.html

UNHCR, (2017). Figures at a Glance. Retrieved from, http://www.unhcr.org/en-au/figures-at-a-glance.html

Randall, Angus. (2018, 16 August), 12yo refugee on hunger strike on Nauru suffering from resignation syndrome, doctors say. ABC News, retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-08-16/12-year-old-refugee-with-resignation-syndrome-on-nauru/10129408

Statistics on people in detention in Australia. (2018, October). Retrieved from https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/getfacts/statistics/aust/asylum-stats/detention-australia-statistics/

Refugee Council of Australia, (2018, October). Refugee Council of Australia factsheet. Retrieved from, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Nauru_201810.pdf

Refugee Council of Australia, (2017, September). What is a Temporary Protection Visa (TPV) or a Safe Haven Enterprise Visa (SHEV)? Retrieved from, https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/getting-help/legal-info/visas/tpv-shev-faqs/

Source:

Source:  Source:

Source: